Why do people put up with sludge?

Anyone who tells you that organizational change is easy is either a liar or a fool. The systems that manage our economy have evolved over the last 150 years, and the social hierarchies that those systems have created continue to dominate many business cultures. For a time, those structures dominate, but environmental factors crop up and tend to disrupt old ways of doing business. It explains why we no longer have Marshal Fields stores in the Midwest and Macy's struggles to compete. Changing market demands and economic conditions require that business organizations adapt. Otherwise, those businesses collapse, forcing something else to take their place. The biggest challenge is taking a legacy business and helping it navigate the change from one set of environmental conditions to the next.

Edward Demming famously said that business survival was not mandatory. It is a deliberate choice to change. What makes that choice so tricky is that plenty of people have a vested personal interest in keeping things the same. Customers may be dissatisfied, and competitors are taking away market share, but as long as the paychecks, bonuses, and dividends keep coming, there is no incentive to change. Change is more frequent than ever, so business people require a more responsive attitude than they did in the past.

Cultural inertia, adherence to outdated processes, and vested interest become sludge you must navigate to get things done. It's a thankless and exhausting process. Innovative business leaders see this and want to remove the sludge. Those who do not are content to see themselves and their organization drown.

Inspiration from my nightstand -

Why anyone would choose to drown is a mystery to me, and then a few books on my nightstand caught my attention. The first is Octavia Butler's "Parable of the Sower." It is the story of an environmental catastrophe told from the perspective of a teenage black girl. The economy has collapsed with petroleum priced out of everyone's reach, clean water is valuable and sold at expensive rates, and communities build walls to keep out looters and thieves. Starvation, crime, and drug abuse are rampant. Butler's protagonist sees the walled community slowly collapsing despite its best efforts. Both her father and brother succumb to violence, and eventually, she leaves her walled community when she turns eighteen.

Much of the first portion of the book is the fight for people to persevere in the face of awful conditions, including growing their food and relying on local militias for self-protection. It also shows that this ingenuity is becoming more futile with the prospect of decreasing resources and increasing desperation. Butler illustrates how some people cling to an impossible situation until it is too late to change or outside forces have made decisions. It is a timely book; I wish someone had exposed it to me sooner.

The other book is "The Unaccountability Machine" by Dan Davis. A former economist and banker, Davis examines why large organizations struggle to make decisions. He also points out how everyone in the organization appears immune to the mistakes and harm caused by a large organization. It is an intriguing thesis, and I look forward to reading it after I finish with Butler. What is very exciting about Davis's book is that it features the philosopher Stafford Beer, whom I blogged about discussing how organizations behave earlier in the year.

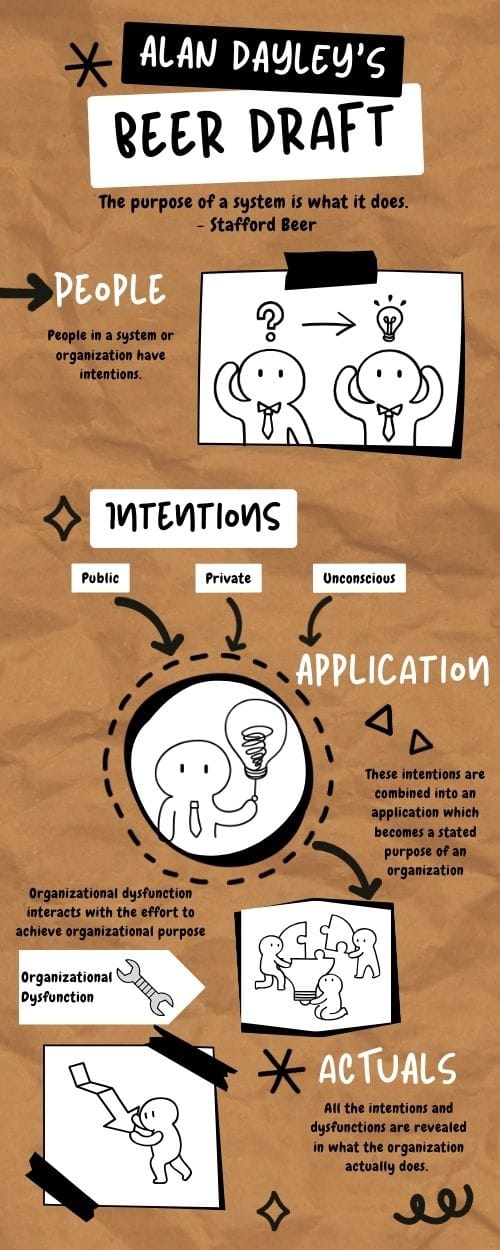

My friends Alan Dayley and Aria Stewart took some of Beer's work and formulated the following argument. First, they start with Beer's postulate: "The purpose of any system is what it does." Notice Beer does not say that the purpose is what people want the system to do. The system exists and does something and may radically differ from its stated intention. It is here where Dayley comes in because he says three forces compete in an organization. These forces are:

- Public intent – what people say to the world.

- Private intent – what people define for themselves.

- Unconscious intent – what people do without knowing.

These three intents combine with the business's organization and create outcomes that may differ significantly from the public intent. Private intent and unconscious intent often sabotage an organization's public purpose. So, executives more interested in creating higher profit margins might undermine the product to extract more money from customers. Unconscious bias influences companies from serving a particular economic group because they do not see them as profitable. There are numerous instances, but you get the idea.

I look forward to reading more of Stafford Beer's ideas and applying them to my agile practice. I better understand why people apply wishful thinking to bleak situations thanks to Buttler and her speculative fiction. Meanwhile, Davis points out in journalistic terms how organizations grow into unaccountability before being crushed by their weight.

From theory to action -

All of this theory and insight is good, but how do we transform it into something that will translate into meaningful change? The first thing we need to do is understand leaders' private intent and their unconscious intent. The best way is to listen to what they say and see if their actions match. If they do not, we have private and unconscious intents that undermine the organization's public mission. It is difficult to do in a community of one hundred people, so it becomes nearly impossible over a government of millions or corporations that pay thousands. It is particularly relevant when we see change work through a system. Vested interests fight to maintain a status quo even if change is being demanded from the top down or the bottom up.

Thus, all change efforts must begin with teaching people why the changes are necessary. It also means how the change will benefit them from a material or security perspective. A manager may hoard resources by not allowing developers to conduct production releases. It is up to senior leadership to let that manager know that DevOps will provide more accountability to the developer teams, free up more time for the manager to do other things, and finally, the expectation for more frequent delivery means the manager must delegate resources to succeed.

There is no magic solution to getting diverse and messy humans pulling in one direction, but change can happen with observation, emotional intelligence, and a few carrots and sticks. We must understand our teams' and their leaders' private and unconscious intent. Otherwise, we risk drowning in the sludge.

Until next time.

Comments ()