The Unwelcome Innovator.

It has been a terrible week. Gun violence has claimed a prominent spokesperson for gun rights, and the internet is awash in anger and recriminations. I have been caught up in it as much as the next person. Once again, I will leave political commentary to those with more experience. I have been in the middle of growing efforts to lead a digital transformation at a manufacturing organization, and the diversion has been a healthy respite from current events.

Jeff Degraff posted an excellent article in Inc. magazine this week, echoing my experience as a technology professional over the last twenty years. I have spoken openly about how organizations often have cultural inertia. If you propose an alternative to the firm's established way of doing things, the firm will see you as a threat and manage you out. It fosters a culture of conformity where people neither invest in the organization's success nor engage in meaningful involvement. They do the work, check off the boxes, and go about their lives. Degraff says this behavior is structural and part of the design of a modern organization. Thus, if you work in business, government, or academia, you will find common threads. Standing out can cause the organization to bring you down.

According to Degraff, the reason for this is the unique nature of innovation, which is conflict, contradiction, and deviance. If you have ever worked in a corporate office, it is obvious that these traits are openly discouraged. Anything new or different needs to fit into the organization. The process smooths down the rough edges. The investments of capital must fit into a spreadsheet, and everything must match the corporate branding. It makes time to market uncomfortably long and drives creative people crazy.

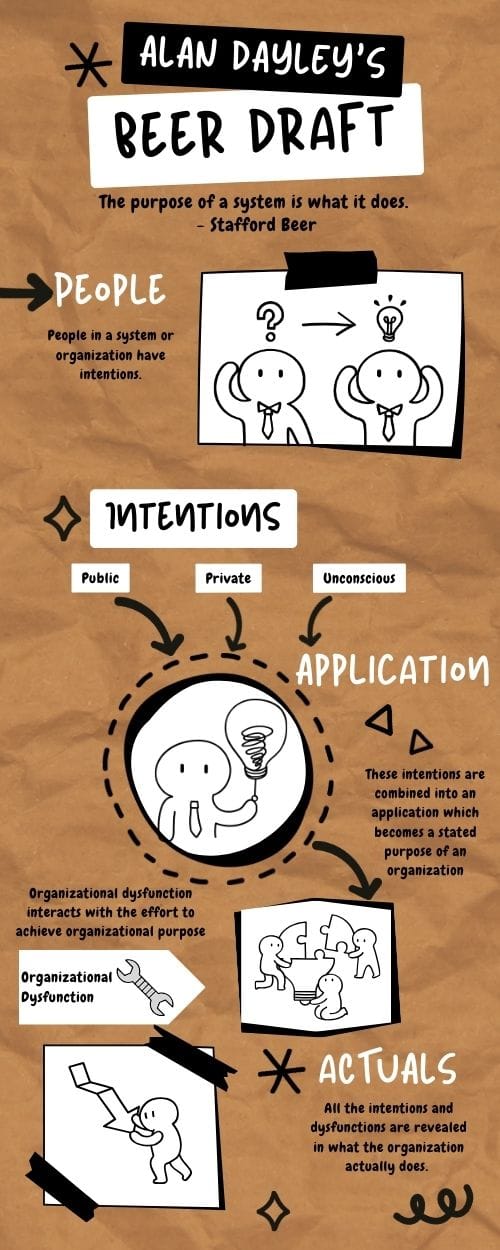

Stanford Beer would say that the purpose of a business is what it does.agile practitioner, you walk the fine line between maintaining continuity and My colleague, Alan Dayley, would add that this reality creates behaviors within the organization that people emulate and promote. The reason is that in business organizations, you want the firm to persist and grow. Anything that threatens these two purposes gets eradicated. It explains why organizations, over time, lose their ability to adapt to market conditions. They are good at something, and they believe that if they maintain that excellence, they will continue to grow. Layers of bureaucracy crop up, and soon the organization becomes feudal, with the most invested in the status quo rising to the top of the organization. The organization desires continuity and gives lip service to creativity and innovation.

In my early career, I believed this trend was driven by malicious intent. Experience has shown me that organizations operate in a way that rewards steady improvement. It is how Kodak became a giant in film development until digital cameras took over. People at Kodak understood the power of digital photography, but could not pivot until it was too late. Although plenty of good people worked at Kodak, the company was too big and too good at film development to change.

It explains why organizations label change agents as deviants. These individuals thrive on conflict, contradiction, and changing the rules of the game. People conditioned to conformity will naturally rebel and attempt to remove these irritants from the system. The trouble is that enforcing continuity is all well and good until it becomes unsustainable, as economist Herbert Stein notes, "If something cannot go on forever, it will stop." The story of Kodak and digital photography illustrates this perfectly.

The modern corporation has crushed countless innovators, and the story of business is littered with their tales. Steve Jobs and Preston Tucker are fine examples, but there are innumerable stories of careers cut short because they found a different or better way to work. As an agile practitioner, you walk the fine line between maintaining continuity and pushing for change.

I wish I had easy answers, but it is clear to me that we are in a situation where Herbert Stein will haunt us. Supply chains must be more resilient and less fragile. The spread of Artificial intelligence is demanding that we get better at our jobs and be more creative. A Large Language Model and an accountant with an inferiority complex will replace us if we don't change. Investors demand more dividends per share. Ultimately, we must determine how to achieve this while managing declining natural resources and navigating economic uncertainty. Change is coming for us, whether we embrace it or are forced into it.

I could be negative about this situation, but I count on Viktor Frankl to help me understand this current moment. As coaches and leaders, we must proceed with a sense of tragic optimism. The business world presents a challenging situation, but we can make a positive impact in individual cases and ultimately scale those solutions to a broader audience. It is not the optimism of unicorns and rainbows but rather the hard, grinding work of smart, dedicated people working together to make a difference.

We aim to be innovators and change-makers, but our organizational structures must prioritize embracing change over continuity. It is a difficult ask, but as Herbert Stein observed, if something is unsustainable, it will eventually end.

Until next time.

Comments ()