The black box of accountability and wildfires.

Working as a coach and scrum master at organizations forces you to confront a few ugly truths. The first is organizational change, which takes time, money, and collaboration. If any of those factors are missing, you are doomed to fail. Next, people want the benefits of change but are often reluctant to change personally to make it happen. Finally, fear and anxiety dominate the offices and cubicles of corporate life. Over my twenty years as a technology professional, I have learned these lessons the hard way. Often, I wonder why corporate organizations struggle with change and providing good outcomes. Thanks to my social group on Mastodon, I was introduced to a book by Dan Davies, who might provide me with some helpful insight, and this week I want to share it with you.

When something goes wrong in a government or corporate context, the public quickly claims that the failure was either a foul-up of immense proportions or a conspiracy of bad actors. The recent wildfires in Los Angeles country illustrate this mindset. Climate change, building in fire-prone areas, and numerous individuals doing things that were individually beneficial but communally disastrous with the addition of one hundred-mile-and-hour Santa Anna winds create a perfect situation for fire to spread and destroy portions of the Los Angeles area. The footage on the news was horrific and reminded me of the climatic parts of Octavia Butler's "Parable of the Sower," where refugees are fleeing fictional southern California wildfires by foot.

The fires were still burning, and people demanded accountability—the severity of the damage singled out Governor Gavin Newsom. Karen Bass, the mayor of Los Angeles, also received criticism for attempting to balance the city budget by cutting back on fire defense, which failed thanks to the pushback of the city council and fire department. Finally, the fire chief was accused of incompetence because she was a gay woman who got her role thanks to diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts. California's elected officials were incompetent in fire prevention or involved in a 'woke' conspiracy to harm property values and public safety. Danvies points to a third alternative to this speculation, which may help better explain the situation and help us transform large organizations. If a white man ran the department, some pundits said the catastrophe would not have happened. Many people wanted to score political points instead of pitching in to help.

California's elected officials were either incompetent in fire prevention or involved in a 'woke' conspiracy to harm property values and public safety. Danvies points to a third alternative to this speculation, which may help better explain the situation and help us transform large organizations.

Davies is not a typical writer. He worked as an economist and investment bank analyst. As a consultant and investigator, he also had intimate knowledge of organizational dysfunction, providing reports on the Libor scandal and the collapse of the Anglo-Irish Bank. In the business world, there is a saying, "You don't call a consultant when things are going well." Davies is one of those people who picks up the phone when business people are in business people are in trouble.

I am only three chapters into his book "The Unaccountability Machine," which is revelatory. First, Davies talks about how complicated the modern government or corporation has become since the Second World War. Much of our frustration with the contemporary world comes from our powerlessness when interacting with gigantic systems. Deliberately over-selling flights frustrates airline travelers when they are bumped. Efforts to provide food stamps or unemployment benefits are frustrated by bureaucratic red tape. Finally, building and zoning laws are intentionally complex, so homeowners and renters cannot hold elected officials accountable for a housing shortage.

The reality of powerlessness before these large organizations creates a feeling of rage. Rage is two different emotions coming together in a volatile mixture. The first is a feeling of injustice—your rights as a customer or citizen are being disregarded. The other is powerlessness. You want to "speak to the manager" or anyone who can help resolve the injustice. If injustice and helplessness build up, it creates what many of us in the software business call a spiral of rage.

It begins at the coffee shop when the server gets your order wrong, escalates when caught in traffic on your way to work, and crests when you receive an email from your boss complaining that you are using a twelve-point Helvetica font in your emails instead of the corporate approved Times New Roman. Situations like this turn us into an irrational monster who wants to lash out emotionally and physically. The people who bear the brunt of the abuse are service and retail workers who often work for large organizations just attempting to do their jobs. Ironically, this creates a spiral of rage for them. It is a miracle that the entire world is not angry daily.

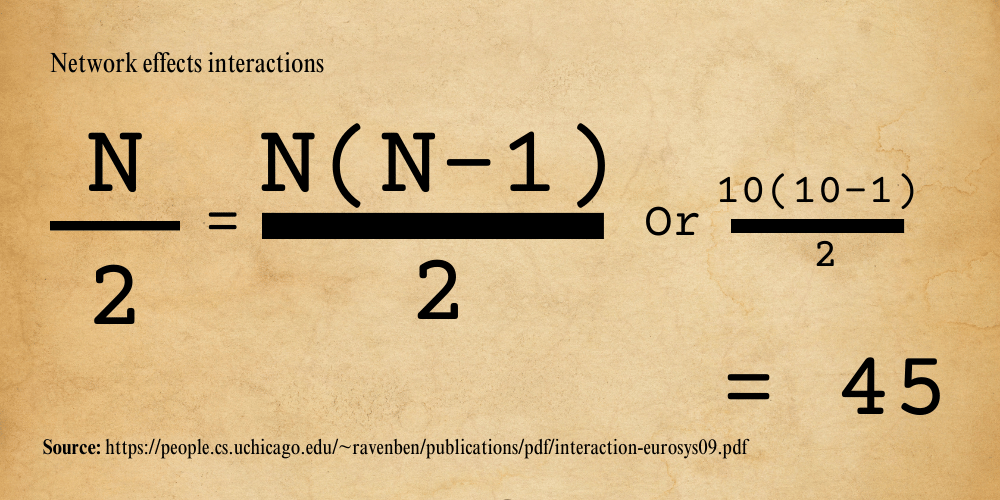

Davis says the source of this rage is that systems get so big and complicated that they start to behave like black boxes, which are impossible to understand from the outside looking in. A group of ten people in a network of interactions and exchanges. The formula for this in organization theory is:

There are at least forty-five different interactions that must take place for information to be exchanged. It does not consider social cues, unwritten rules of conduct, and differences in power and prestige. Thus, it isn't easy to understand the behavior of a system of ten people. Now, multiply this math by thousands and tens of thousands of people. We are quickly attempting to deal with large numbers of countless connections, and soon, it becomes impossible for an outside observer to understand the system's operation. It becomes a black box.

Davies says the following, with emphasis mine,

"The extent to which individual accountability can exist in a system is dependent on the extent to which you treat it as a black box which when you do when something is too complex to deal with any other way."

The world around us is a black box we do not understand from our local governments, the businesses we rely on, and the organizations we work for, and that creates a further cycle of rage. The fire fighting services in and around Los Angeles County are complicated systems with plenty of specialists and millions of dollars in taxpayer-funded equipment, and they depend on builders and individuals to respect the basics of fire safety. It is a textbook example of a black box.

Davies then cites the work of consultant, philosopher, and social theorist Stanford Beer, who is known for the maxim, "The purpose of a system is what it does." Looking from the outside, the fire department had a specific purpose: to protect individual properties from fire and prevent its spread to other buildings. Efficiently constructed to operate under normal conditions, the Los Angeles County Fire Department was overwhelmed by a firestorm fueled by global warming and overconstruction, despite heroic efforts on the ground, as it threatened entire neighborhoods.

The system, a black box with thousands of people and millions of internal interactions, attempted to address a situation outside its purpose. Naturally, it failed. So, this was not the result of a conspiracy or an example of incompetence. It did not result from a conspiracy or incompetence. Instead, an organization attempted something it was not designed to do or tried to achieve an impossible result.

From the agile/scrum perspective, this means that instead of examining an organization's black box, we need to understand how it operates as a whole, as Dan Davies explains.

"If you are trying to understand a system, all you can do is observe its behavior, and whatever you can learn from doing so is all there is to know about it."

So, suppose your organization is terrible at product development, customer satisfaction, or maintaining profits. In that case, it is because, over time, the organization decided as a decision-making system that these things were not essential and organized around its purpose, which it excels. As coaches and business professionals, we should look at the people and systems we set up instead of looking for messengers to shoot and people to hold accountable. It's easier to fire an engineer who makes a mistake or a salesperson who cannot close clients. Still, a systematic approach is going to yield better results long term than metaphorically kicking butt and taking names. Edward Demming said it best: " A bad system will always defeat a good person."

The Los Angeles wildfires are a human and economic catastrophe. Blaming them solely on California's liberal institutions is simplistic and short-sided. They are also instructive examples of Dan Davies and Stanford Beers' understanding of organizational behavior and how we in the agile community must approach organizational change.

Failure to do so will trigger another spiral of rage.

Until next time.

Comments ()